Defining the Question

So what makes a game successful on Steam? There are a lot of ways to define ‘success’, so for now let’s focus on how many hours players sink into their titles.

Exploring the Question

I’m not sure how much of the population is like me. I’ve lost track of the number of times where I’ve loaded up Steam, extremely bored, and started flipping through their splash page of ‘PLEASE DOWNLOAD ME!’ games. There’s almost always a sale. Something catches my eye, I click on it. The game looks interesting, I check the price, I argue with myself. I make some very compelling points, and I treat myself to a new game. And yet, after installing the game, I’ll sink maybe two to five hours into it before losing interest and sacking it for a return to my old classics. I mean, I have to be an aberrant, right? I’m the guy that has like five-thousand hours tied up in the Civilization series.

Well, let’s sooth my suddenly rising concerns that I’m alone in this.

The Data

After poking around for a bit, I found a few data sets that had more or less everything I needed to write a compelling point about my own habits. The first dataset is a break-down of a sampling for 200k Steam users, new games they bought, and how many hours they spent playing the titles. The other next dataset and it had a wealth of data, like the price of the title, some review data, release dates, and the genres tags from Steam.

Shaping the Data

My shaping and visualization notebook can be found here for those wanting to follow-along at home. Our first dataset was pretty clean already. There was an extra column, which was dropped easy enough. The second dataset was a bit more clunky with a lot of data that I don’t need. I shave off a few of the items that I don’t particularly care about for this exploration (like publisher and platform data). I merged the two datasets. The first dataset had some double entries since the play/purchase was a single column and if they played it reported 1.0 hours in the hours played column.

Then I did a hard look at the data again and found some very big errors that were going to taint my results. Many of the game titles hadn’t translated corrected due to minor differences between the two sets of data. Primarily this was around sequel-like titles that included punctuation differences, or trademark style symbols like in the Call of Duty or Civilization series titles. I spent a few hours going through the top 30 games from the first data set to ensure that the metrics that I wanted were clear. While there was a sizeable portion of data lost, this was mostly for minor titles, and nothing in the top 20, which is where I was focusing my efforts anyway. Not wanting to confuse things further, I also filtered out the purchased aspects of this for a new dataframe and then I explored the data a bit.

Explaining the Data

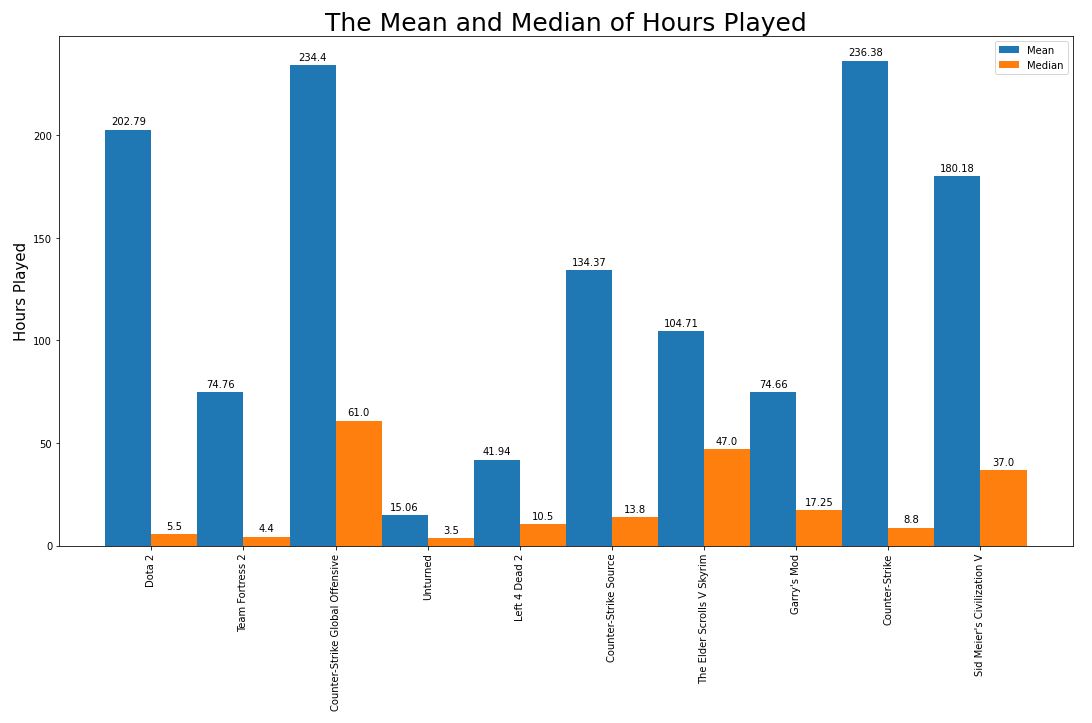

The first thing that I really noticed was the age of some of these games. Counter-Strike makes it into the top ten based on my filtering, and that game came out in 2000! After several hours of hammering away at these datasets, I was able to refine myself to this clean display:

Not the prettiest, I know, but it contains a lot of interesting, and at least to me, surprising data. I want to focus on two areas that jumped out at me, and then I want to sum this up with some annidotal thoughts on it. First, let’s look at the hours people sunk into these titles.

Notice that every single one of these titles has a huge difference between the Mean and Median time spent playing them. When I was first exploring this data, I was just going to go with the Mean as my metric, until I took a closer look at the data. Some players sunk an unbelievable amount of time into these titles. One player in Dota 2 had nearly two-thousand hours in just that game alone! It felt a little jarring, but when you look at the Median player’s time in the games, you’ll notice that it’s a much more uniform distribution.

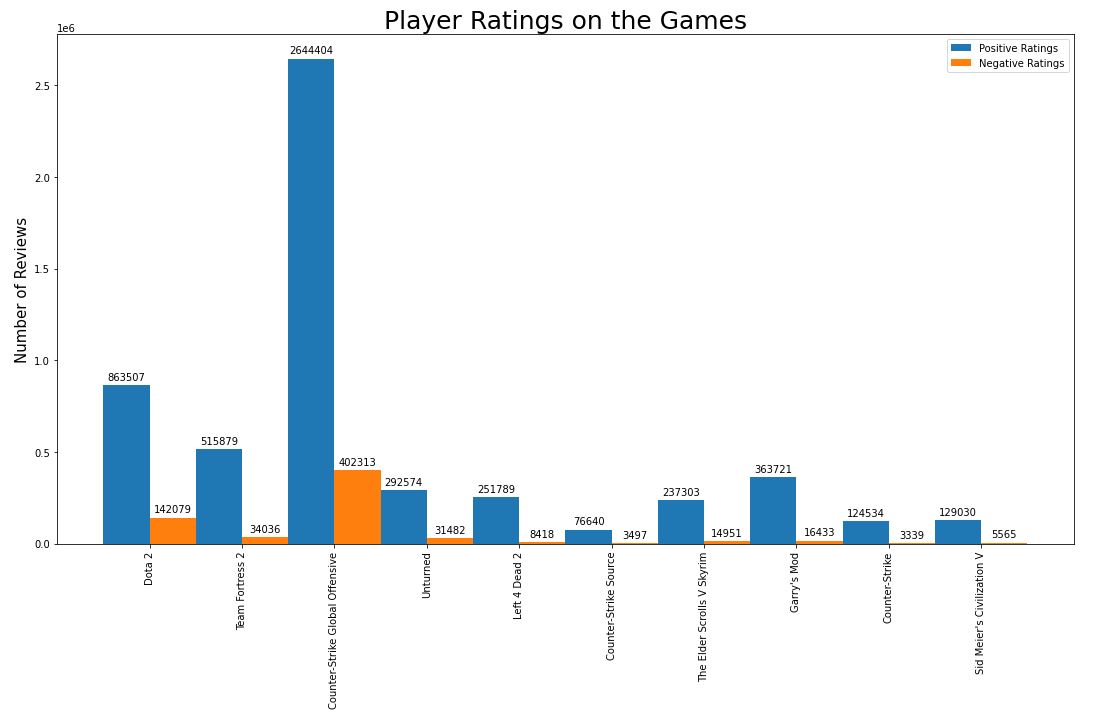

The second thing that I want to focus on are the reviews for these games.

I would have expected there to be a stronger correlation between positive reviews and hours the players invested into the game. While all of these games have a very high percentage of positive to negative reviews, you’ll notice that the sheer amount of reviews vary wildly. There does seem to be some correlation between the median amount of time that people spend in games and amount of positive reviews, but not enough to pin down.

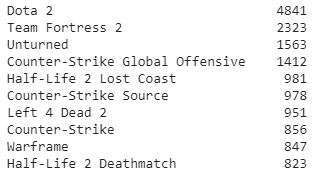

As something of a sanity check, I went through the top 10 purchased titles for the same period, and came up with this:

What is most surprising to me here is that Counter-Strike, plain old vanilla Counter-Strike, still ends up in the top 10 most purchased list. That means that this nearly two decade old title was still drawing new purchases in addition to having a clearly rabid fanbase.

Conclusion

My first take-away from this is to breathe a huge sigh of relief and realize that I’m not alone in my gaming habits. It seems like a high percentage of players, if not the majority, will buy a title and not invest too much time into it. This makes me think that Steam is the gamer-equivalent of a gym membership: you purchase it and never really use it after that. But back to the question: What makes a game successful on Steam?

It seems to break down into four major categories.

- The title needs to be affordable. The top four slots are free-to-play titles, and the next five are under $10. That’s bonkers, when you really think about it.

- It needs to include the ‘Action’ tag for the Genre. 7/10 of the list included the ‘Action’ tag.

- It needs to have a high ‘replay’ factor. Consider the age of these titles. Half of them weren’t even released this decade, and one was released back in 2000. That tells me that there is a mix of nostalgia for sure, but these games also need to have some staying power. This is probably the hardest thing to pin-down, but a lot of these games also have multiplayer group v group round style play for quick pick up games and low investment rounds.

- Your title needs to have a lot of positive reviews. Word of mouth seems to be far more effective than advertising dollars. Games that have been out for awhile don’t have people spending money to hype them up. They make their own sauce, as it were. If you have a game that people like, that momentum will carry them forward for many years to come. Look at Counter-Strike Global Offensive. This title is free, came out in 2012, and has 2.6 million positive reviews. That’s not advertising you can buy.